Bees are valuable insects from an economic perspective because they pollinate crops and produce other useful items such as honey, beewax, and bee venom . The honey bees of the Apis genus are social insects that dwell in highly organised communities. Despite their significant benefits to crops and humans, bees can pose a threat because of their ability to deliver painful and toxic stings. In most cases, honey bees display non-aggressive behaviour towards humans and only resort to attacking when they perceive a threat. Male drone bees, larger than the females, lack stingers. Only female worker bees possess the ability to sting, use a modified ovipositor as their stinger. Bees die after stinging because their stingers get stuck in the skin of the victim and are pulled off the bee’s lower body.

A mature defender bee (performs guard duty) or forager bee (explores for nectar and pollen) contains approximately 100–150 μg of venom, and it injects 0.15–0.30 mg of venom through its stinger. In comparison, a honeybee can inject 0.1 mg of venom. The toxicity of extracted venom can last for years if properly preserved to avoid oxidation The queen bee’s venom production is highest when she first emerges, so she is well equipped for the battles she will fight with other queens; a young queen can produce around 700 μg of venom (Benton and Morse 1968).

Apitherapy is a form of alternative therapy that uses bee products for medical purposes and is gaining popularity due to its health benefits.

Study Area: Dimapur

I conducted the study at the apiary at St. Joseph University, Ikishe Village, Dimapur. Nagaland, India, where the Zoology Department rears honeybees for educational purposes only. The study area is rich in biodiversity, with many flowering plants and trees around the campus providing good nectar sources for the bees. The average temperature in Dimapur is 22.6°C, and the average annual rainfall is approximately 1710 mm. August is the hottest month of the year, with temperatures varying from 21.6°C to 32.7°C.

Bee Venom Collection

My fieldwork took place over five months—January to May 2024. In the apiary, bee venom was collected, using a Model Bee Venom Collector, from Hive 1 (full entrance opening for large colony) and Hive 2 (normal entrance for small colony). I observed and studied the venom samples from both hives.

How a Model Bee Venom Extractor Works

The bee venom extractor used in this research is based on a simple open electrical circuit, where the flow of the electrons has been interrupted or ‘opened’ at some point so that current will not flow.

The venom collector was made using wood and plywood to construct the two borders and the base-end of the model, respectively. To create the open circuit arrangement, alternate positive and negative wires were laid parallel and approximately 5 mm from each other. A 12-volt battery was used to power the device. A glass pane was kept beneath the wires to collect the bee venom. When bees touched both the positive and negative wires simultaneously, they completed the circuit and enabled the current to flow. The flow of current tricks the bees, and they tend to sting on the glass pane, releasing their venom. The bees do not die in the process because their stings remain within their bodies.

Extractor with the wires placed approx. 5mm apart. Khrieletuonuo Yhome

Electrical Extraction of Bee Venom

The bee venom collection tray was placed at the hive entrance, and a mild intermittent electric shock of 12 V was applied through wires above the collecting tray. Bees coming out through the entrance or guarding the entrance touched the wire grids and were shocked. This created a massive defence response in the worker bees, and they stung the surface of the collector aggressively. Liquid venom was deposited on the glass plate, drying immediately after deposition. This dried venom was then scraped off and taken to the laboratory, following recommended precautions. The dried venom powder was then stored in a dark-coloured bottle or a sample container wrapped in aluminium foil in a freezer at -10°C to protect it from degradation due to sunlight.

Precautions During Electrical Bee Venom Extraction

Extreme caution should be taken when handling bee venom.

- Use gloves and eye/mouth protection.

- Avoid ingestion or inhalation of bee venom.

- Cover any exposed cuts or grazes on your hands or body.

- Handle the venom collector with care because remnants of venom will be left on the device after collection.

- Wipe the collection plate with rubbing alcohol (or similar non-residual cleaner) after and prior to venom collection.

Effects of bee venom

Apitherapy involving bee venom has been utilised for centuries for pain relief. On the other hand, an allergy to honeybee venom can lead to a dangerous and potentially life-threatening anaphylactic reaction after a sting. The potency and effects of the venom of stinging insects vary between species, causing different reactions in the human body. Every time I go to extract bee venom, I get stung in an exposed area of my body, usually my hands. It does not feel unduly itchy on the first day; however, on the second day, the intensity increases, accompanied by swelling and redness. But I have learned that not everyone suffers from the same level of itching, swelling, and redness as I do. The most striking effect is that my appetite improves after every bee sting. Interestingly, beekeepers have lower rates of all cancers than the general population (Mcdonald and Mehta 1979).

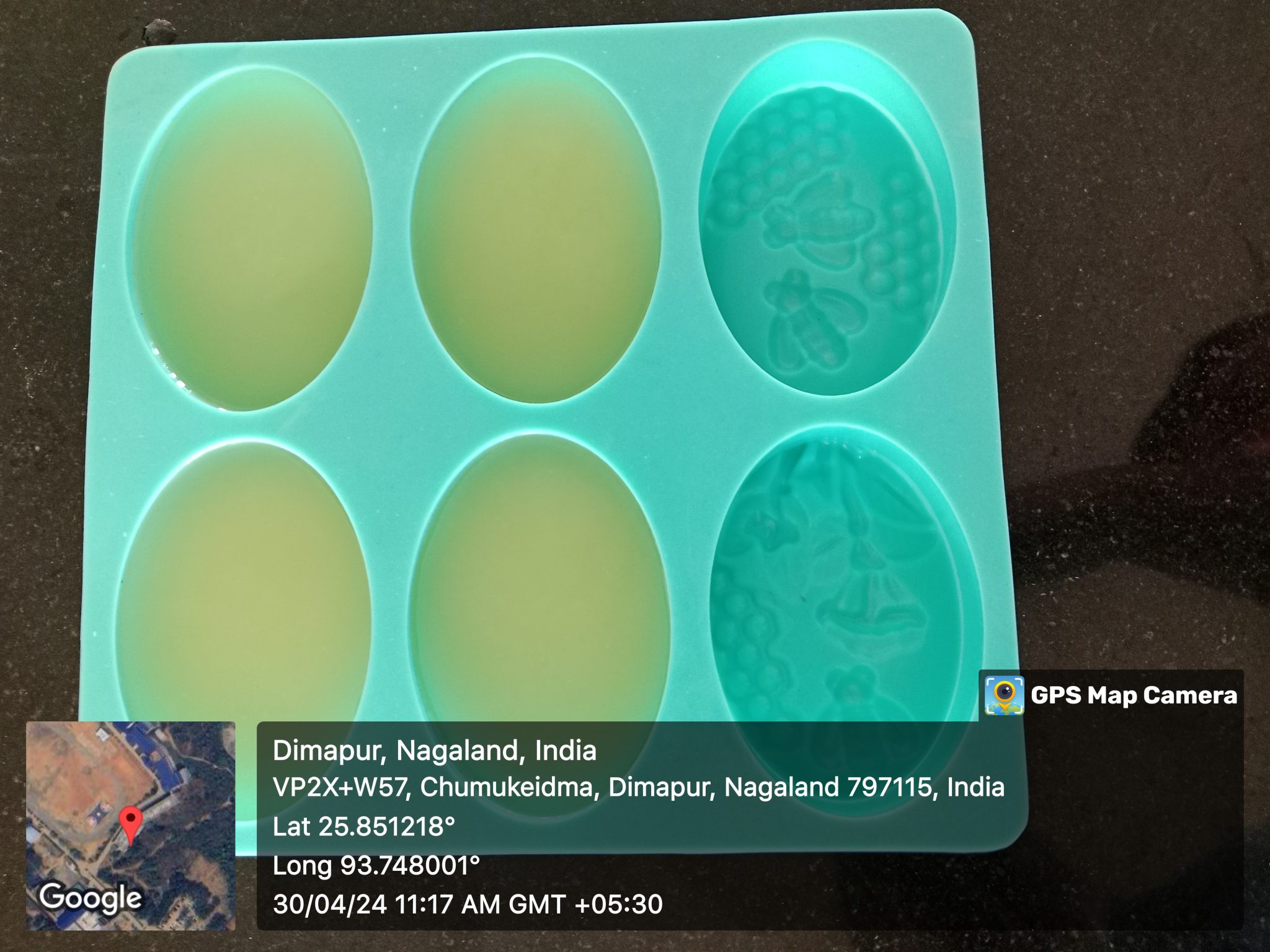

The collected venom was then used in soap production for its potent antimicrobial properties, aimed at combating skin infections by fungi and bacteria. By using venom in soap production, a bioactive substance in venom is repurposed to offer therapeutic benefits for skincare.

Bee Venom in Soap Making: The Cold Process

In my study, I used the cold process for soap-making. One of the advantages of this process is that it allows full control over the product, including the soap’s scent and appearance. The cold process begins with preparing a lye solution (sodium hydroxide) by mixing with water, to which oils (coconut oil 133 g and olive oil 67 g) are added. The oils must be carefully blended and once thoroughly mixed; additional ingredients such as bee venom (0.50 g in 260 ml of soap solution) or fragrances can then be added according to preference. The resulting solution is poured into moulds and left to cool and harden into a cake of soap. The pH of the soap is then measured after two weeks; a pH of 9.61 is ideal for skin.

Bee venom soap. PC- Khrieletuonuo Yhome

Collection of Bee venom: February to April

The amounts of venom collected varied over the study period. The total monthly extraction amount was highest in April (0.28 g). More specifically, the highest level of bee venom in one sample (0.12 g). was extracted from Hive 1 between 9:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. (local time) in April (01/04/24).

The total monthly extraction amount was lowest in February (0.08 g). More specifically, the lowest level of bee venom in one sample (0.01 g). was extracted from Hive 2 between 01:40 p.m. and 12:40 p.m. (local time) in March (27/03/24).

Studies on the peak venom-yielding hour of the day revealed that the maximum quantity of bee venom was obtained between 9:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. The spike in the venom yield at this time coincided with peak hive activity and the high number of bees present in the hives after their foraging activities.

The total amount of bee venom collected within a period of three months was 0.55 g. Just three bees died during the study.

Conclusion

The perceived health and economic advantages of bee venom have driven an increasing level of interest in bee-venom research among beekeepers and scientists. Indeed, by utilising bee venom as a potential revenue stream, farmers can enhance their income. However, it is crucial to collect the venom in a manner that maximises yield without causing harm to the bees or disrupting their other hive activities; in my study only three bees died. Moreover, careful handling is essential to prevent the venom from being contaminated by unwanted dust particles and pollen. In this study, the colony was small and had only a few bee hives; therefore, bee venom could not be collected easily; it required several attempts to collect a small amount of bee venom.

The development of specially designed bee-venom collectors represents a breakthrough in the protection of bees during venom extraction. Furthermore, research focusing on determining the optimal duration and peak hours for venom extraction can aid farmers in maximising their yield without compromising the production of honey or pollen.

Using bee venom to make soap could enhance the income of a bee keeper. However, more research is needed on how to make soaps that maximise the antibacterial and antifungal properties of the venom.

References

- A.W. Benton and R.A. Morse, “Venom toxicity and proteins of the genus Apis”. J. Apic. Res.; 7(3): 113–118, 1968.)

- Mcdonald, JA., Li, FP. and Mehta, CR., Cancer mortality among beekeepers. Journal of Occupational Medicine 1979; 21: 811-81

Apis cerana Bee Venom and Its Application in Soap Making

By Khrieletuonuo Yhome

Summer School 2024, Foundation Track Scholar