“We had to walk for two days to reach Noklak,” my mother would say when we were little and living in Nagaland, India. She belongs to the Khiamniungan Naga tribe and was raised over the border in Myanmar. Like many others, my mother came to India for education and eventually settled there. Since 1967, the Khiamniungan tribe has been split between the two modern countries of India and Myanmar, with more than half of the population in Myanmar.

I was born and raised in Kohima, Nagaland, where we frequently hosted people from my mother’s village across the border. I vividly recall waking up in the dead of night, eagerly rubbing my eyes to see our guests, but mostly eager to see what they had brought. It was always exciting. They would bring chicken in a bamboo basket, smoked venison and bushmeat, aromatic Sichuan pepper, intricately woven Naga baskets, mats made of cane, and beautiful ornaments.

The guests’ journeys were arduous, including two days traversing rugged mountains and a day’s bus ride to reach Kohima; they came for trade, medical treatments, or occasionally, to entrust their children to affluent households as helpers in exchange for education. For those with nimble feet, Noklak could be reached in just a day.

For my siblings and me, the following days would include a series of fascinating stories about were-tigers and spirits rumored to snatch away village children. For our parents, it was a more somber affair, exchanging news about who was alive, who was ailing, and who had passed away. With no Internet connections in the village, our only means of staying informed about distant relatives was through occasional visitors. To me, these were stories of a distant world. The village, its houses, and its people only existed like a painted picture in my head.

I never saw my ancestral village because it lies in an undeveloped part of Myanmar where, even now, there are no proper roads. I remember my sister telling me upon her return from the village that an elderly man had asked her, “People who went to town came and told us that the roads are very wide and covered in black; is it true?” As I grew up, I had the chance to visit other cities in India for studies and tours, but I always felt a sense of detachment from the land of my origins.

Going Home

Last year, in March 2023, we had the chance to visit Noklak as a Canada-IDRC Myanmar Research Fellow on the “Earthkeepers” project. Noklak is a district in the eastern part of Nagaland that abuts the Indo-Myanmar border and is predominantly inhabited by the Khiamniungan tribe. The preliminary fieldwork aimed to establish relationships with the communities, introduce our work, and broadly assess the local farmers’ understanding and experience of global climate change.

My team and I hopped into our faithful Gypsy(SUV) and headed out for our first fieldwork. The tightly packed streets gave way to scattered houses, and the forest greeted us as we drove further. Along our route, we traversed numerous villages and small settlements, often finding ourselves surrounded by nothing but towering mountains and lush foliage, with few signs of human presence between these remote outposts.

Upon reaching Noklak, I was immediately struck by the fact that I could understand every word spoken around me, everyone spoke the Khiamniungan language. I found it amusing, because in Kohima, only a minute proportion of the population conversed in the language, and the chance of hearing it spoken on the streets was rare. This moment marked the beginning of my journey to uncover and embrace my cultural roots.

In the following days, we travelled to four different villages under Noklak— Dan, Wui, Peshu, and Langnok. Of the four villages, only Peshu did not share a boundary with Myanmar. The villagers welcomed us very warmly. Beyond Noklak town, the paved road disappeared; narrow and dusty roads led us to the villages. The unforgiving sun was high up in the sky— a little too warm for April, we thought. We learned that these roads become treacherously difficult to navigate during the rainy season and envisioned the challenges posed by the muddy, slippery terrain and the perilous cliffs.

The houses in the villages were typically constructed from wood or bamboo, with roofs made from palm thatch or tin. Churches were often the only cement structures. However, in Peshu village, we observed that stone slates were used for roofing, a typical feature of traditional Khiamniungan homes. The granaries in the villages were built in a similar style to the houses, mostly situated a short distance away from the main dwellings. They are lifted from the ground with poles to protect the grains from rodents and insects.

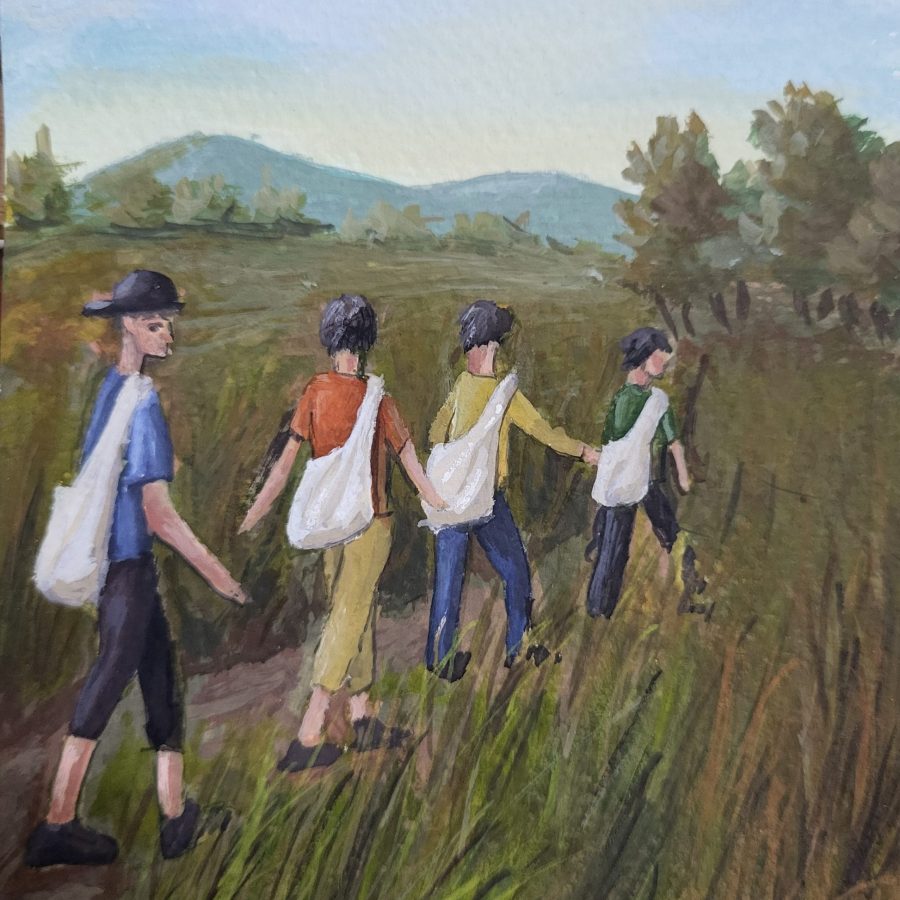

In Dan Village, we observed young boys carrying sling bags traversing the porous border through thick, overgrown grass. These boys crossed into Noklak from the Myanmar side to earn daily wages, often making around 200 rupees a day.

The Border Barrier

The border defied any conventional image we might have in our minds; instead of clear demarcations, it was marked by just a few pillars in specific areas, serving as boundary indicators. If asked how they discerned Myanmar’s territory, locals would point to landmarks such as a tree, a stone, or a mountain. The Khiamniungan community has shown strong resistance against the border demarcation efforts, dismantling the border pillars and even destroying barricades erected by the Indian military. An unfinished border fence still stands at Dan, telling the story of the community’s resistance. Although the village is located within Indian territory, its fields extend into Myanmar, requiring daily border crossings.

The villagers escorted us across the border to visit several historic landmarks and structures dating back to World War II (WWII), such as bunkers and a helipad. Nyukha, the village Gaonbura in his 80’s¹ , pointed to the aeroplane crash site, vividly recounting the time he assisted in rescuing soldiers. His sharp memory made the event feel as if it had happened just yesterday. But the once prominent site is now swallowed by the dense forest. The village lies along the notorious route nicknamed “The Hump” by the American pilots. This route was used for flying supplies from India to the forces resisting the Japanese in China. Many planes crashed as they crossed the perilous mountains, and one of the most famous crashes occurred at Pangsha (Dan) on August 2, 1943.

Again, in Langnok village, we saw women and children carrying goods from Myanmar in their baskets to sell in India, undertaking a gruelling two-day journey on foot. With no road connections, some rely on sturdy Burmese mountain bikes to traverse the mountainous terrain. However, many cannot afford the fare due to the high cost, forcing them to embark on days-long walks instead. These bikes lack registration plates and are restricted from travelling further into India beyond Noklak.

From our many conversations, I realised that I did not know how to say words like “harvest,” “sowing season,” “granary,” “rivers,” and the names of crops and animals in my native language. It was striking to observe how different the conversations in rural villages were from those taking place in urban settings.

Climate Change Effects

All the villages reported experiencing the effects of climate change, noting irregular rainfall patterns and a rise in temperatures. Consequently, crop yields have been declining. “We used to predict the weather from the position of the sunrise beyond Mount Khülio-King, but now the rains arrive unpredictably, and it’s challenging to tell the weather.” the Gaonbura of Wui village told us.

Peshu was the most experimental of the villages, with farmers planting different crop varieties in different seasons and fields to see how they thrived. The villagers told us that they first noticed the change in climate in 2003. We found the authorities had failed to inform the farmers that the transformations they witnessed were part of a larger global phenomenon. The local community attributed the observed changes to the ongoing road construction. This lack of communication underscored the disconnect between policymakers and the grassroots.

Our objective was not to teach about climate change, as the local communities possessed a deeper understanding of their crops, soil, rainfall patterns, and weather conditions than we did. Rather, our goal was to listen and learn from their experiences, to understand their perspectives, and to explore how they are adapting to these changes. We recognise the value of indigenous knowledge and its potential contribution to addressing the broader climate crisis.

This fieldwork has been a profound exploration of identity and belonging, I met many friends of my parents who recounted some cherished memories. From the Khiamniungan villages, we have witnessed the unwavering resilience of the community.

In these unfamiliar hills, where I have no stories of my own to tell, I’ve sometimes grappled with a sense of detachment but I always felt deep down that this place is home. In the embrace of the lush landscape, the rugged terrain, and the warm hospitality of the people, I have learned that home is not always a place but a feeling deeply rooted within us. It is a connection to our heritage, the shared memories of generations past; it is a sense of belonging.

Home is wherever our journey of self-discovery leads us.

¹The institution of Gaonbura dates back to the colonial era, when the British appointed influential

persons in villages to oversee matters relating to land and revenue in a particular area (Wouters 2018,

129). Today, Gaonburas have fewer powers but act as custodians of customary law and order.

References

Glines, V. C. (1991). Flying the Hump. Air and Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.airandspacefo ces.com/article/0391hump/

David, S. (2016). The Hump: Death and Salvation on the Aluminum Trail. HistoryNet. Retrieved from https://www.historynet.co /salvation-hump-wwii/ Wouters, Jelle J. P. (2018). ‘Performing Democracy in Nagaland: Past Polities and Present Politics’. In Democracy in Nagaland: Tribes, Traditions, and Tensions, edited by Jelle J. P. Wouters and Z. Tunyi, 123–40. Kohima, Thimphu, Edinburgh: Highlander Books.

The Call of Home: Rediscovering my Roots on the Indo-Myanmar Border

By Saktum Wonti

Canada-IDRC

Myanmar Research Fellow